The History of Trance

1988 - 2006

Grounded in German techno and British rave culture, trance first emerged in the late 1980s and grew into the 90s’ most popular form of electronic music, reaching peak commercial success at the turn of the new millennium.

Through its rich and lengthy history, trance has been responsible for some of the world’s most groundbreaking dance records, elevating DJs to almost god-like status, before suffering an inevitable decline in popularity.

This is the story of how it all happened.

Give Trance A Chance - The Mix Series - Episode 16

On this 16th edition, it’s our pleasure to hand over the turntables to one of France’s busiest and fastest rising Djs, Angie. Co-founder of the Female electronic music collective Club Sauvage and Régalade Paris, she’s no stranger to 90's rave, trance, progressive and everything in between and so, across the next 60 minutes, expect a banging mix of classic trance anthems.Tracklist available here.

The Origins of Trance

Before trance music was labelled as such, other forms of electronic music—most notably acid house and techno—served as precursors to its birth.

The origins of trance music can be traced back to Germany during the late 80s and early 90s, when European DJs and producers began to incorporate electronic and psychedelic sounds into their music.

At this time, Detroit techno was making its way to Europe, where many German and UK producers used it to create a more atmospheric sound. During these formative years, many people called the genre ‘techno trance’ or even ‘trance dance,’ with early trance mix tapes circulating among enthusiasts, helping to spread the sound to a wider audience.

The label “trance” as applied to music may stem from the emotional feelings it induces—the high euphoria, chills and uplifting rush experienced by its listeners—or it may indicate the real trance-like state that the earliest forms of the sound attempted to emulate in the 90s, before the focus of the genre changed.

Sven Väth and Techno Trance

Sven Väth has long been an ambassador of German techno with his globetrotting label, Cocoon. In the early 90s, he was the co-owner and founder of Harthouse Records, as well as a stalwart resident at the now-defunct Frankfurt-based club Dorian Gray, which is widely considered one of the most important places in the origins of trance. On his seminal album, ‘Accident in Paradise’, Sven combined techno with more melodic themes and classical influences to create a symphony of emotion.

Some other examples of early trance records include KLF’s 1988 release ‘What Time Is Love’ (Pure Trance 1). Many people consider this to be the very first trance track.

German duo, Dance 2 Trance, form a critical reference point in the origins of trance with their 1990 track ‘We Came in Peace’.

In 1991, Future Sound of London released ‘Papua New Guinea’. This was essentially a breakbeat techno track that differed from the norm in its featuring of uplifting atmospheric pad sounds in lieu of the customary rave stabs or piano riff samples.

Arguably, the genre’s first breakout hit came when another German duo, Jam & Spoon, remixed their 1990 single ‘The Age Of Love’, in 1992. This is a timeless classic that still holds court today and has a special place in many DJs’ record boxes.

In 1992, Jam and Spoon continued in euphoric form with the release of their progressive trance masterpiece, ‘Stella’.

German techno group Hardfloor released ‘Acperience’ in 1992, selling over 30,000 copies in Britain alone. The track is a piercing acid house cut which places a greater focus on melody than traditional acid house, leading to its dual categorisation as both Acid and Hard Trance.

Hardfloor took this concept even further on their 1994 tracks ‘Into Nature’ and ‘Fish and Chips’, released on Sven Väth’s very own Harthouse label.

Quench released ‘Dreams’ in 1993, which became a massive club hit and received airplay on Pete Tong’s BBC Radio 1 show throughout December 1993.‘Dreams’ is an early example of a trance track which combined atmospheric pads with filtered sawtooth* synthesiser riffs, a technique which became more commonplace towards the end of the decade.

More typical of the proto trance sound of that time is the vocal mix featured in ‘Celebrate’ by Miro; the filter sweeps were not yet present, but ‘Celebrate’ boasts an infectious lead riff repeated over gradually layered synth pads and a bassline key change. Techniques like these were later employed by trance producers to create the genre’s trademark hypnotic feel.

As the 90s progressed, and these first forms of trance music emerged in Germany and the UK, a dance music revolution was beginning to take shape.

Episode 18. CRO - Hard Trance Classics

On this 18th edition, we are diving deep into the harder styles of trance with CRO. A Dj from the Netherlands with a deep knowledge and passion with hard trance classics around the turn of the millennium. Expect blistering tracks from Dumonde, Emanuel Top and Signum to name but a few.

1994: The Birth of Goa Trance

While trance music was developing across Europe, it was also gathering a following in the Indian state of Goa, which had been a popular destination for psychedelic music since the late 1960s.

DJs in Goa had switched from playing psychedelic rock to electronic music during the 1980s, discovering that early trance music perfectly fitted with the hypnotic, hallucinogenic-based Goa scene.

Goa was integral to the development of trance, as DJs from all over the world brought their many influences and sounds to India. People were playing industrial/EBM, techno, synthpop, Detroit techno, German trance, etc. — basically whatever they felt like. Through this amalgamation of sound and spiritual culture, Goa trance was born.

By 1994, Goa had developed its own unique subgenre of trance music, which it began to export to Europe and the UK. Artists such as Man With No Name received playtime from world-renowned DJ Paul Oakenfold, whose timeless album, ‘Goa Mix,’ became one of the most influential trance mix releases of the time, played a pivotal role in popularizing Goa Trance

From the late 90s onwards, Goa trance formed the basis for this widely popular subgenre, known as “psytrance” or “psychedelic trance”. This eventually grew into a genre and entity of its own, making it impossible to cover comprehensively in this article. If you’re interested in reading more about this, please check out http://psytranceguide.com/.

Trance in the Mid-90s

While jungle, piano house, and UK garage largely dominated British clubs during the mid-1990s, trance music continued to develop strongly in continental Europe, particularly across Germany. Early trance featured many elements of then-current European commercial rave and techno music, with tracks such as ‘Tears Don’t Lie’ (1995) by German DJ Mark’Oh beginning to take on the stuttering, gated synthesiser chords later associated with trance.

In 1995, Italian producer Robert Miles released the infamous ‘Children’, a track which features classical-style piano and strings, alongside the gated trance pads which helped to kickstart the subgenre known as “dream trance”.

Meanwhile, in the UK, some house and techno producers began to pick up on the fast-emerging trance sound coming from the continent and incorporated it into their tracks. JX – ‘You Belong To Me (No Respect Remix)’ (1995) is a great example of the early UK trance sound.

This particular style, which was eventually labelled “Nu-NRG”, became increasingly faster and harder, while taking on new musical elements such as the ubiquitous 90s rave sound of the Roland Alpha Juno 2 “hoover”, which synthesises noises and off-beat bass stabs.

By 1996, trance music was becoming a major force on the European club circuit and had also started to make a huge impression on the UK club scene. During this year, the highly-regarded Additive label (a sublabel of EMI) was launched, bringing trance to a wider UK audience. The label’s first year saw high profile releases such as X-Cabs – ‘Neuro’.

Also in 1996, Chicane released ‘Offshore’, a record which was to become a cornerstone of trance music, making haunting synthesiser pads a key feature of the genre from that point on.

That same year, Dutch trance producer Ferry Corsten released his first single under the Moonman alias, ‘Don’t Be Afraid’. Much like Chicane, Corsten also had a considerable and undeniable influence on trance music, helping it to become the global phenomenon that it was in the late 1990s.

Corsten’s remix of Marc Et Claude’s ‘La’ in 1997 introduced a more prominent kick drum alongside the sawtooth synthesiser chord stabs. This later became a key element of the big room trance sound, which was the electronic music of choice around the turn of the millennium.

The Rise of Progressive Trance

In what could be considered the second major subgenre split (the first being Goa trance), the rise of progressive trance occurred around the same time as the development of the harder, faster styles of trance being pushed by Corsten and co.

Progressive trance contains elements of house, techno, and ambient genres. It features longer build ups and more subtle breakdowns, without the use of the high-pitched blaring synths that the big room sound made famous.

During the 90s, progressive house and progressive trance existed in harmony, often blending seamlessly in a well-curated trance mix, providing a deeper, more atmospheric experience. However, the two styles do have notable differences; progressive trance generally features louder kicks than progressive house, and focuses more on arpeggios, delays, gated synths, and heavy reverb, with a broader BPM range of 130-140.

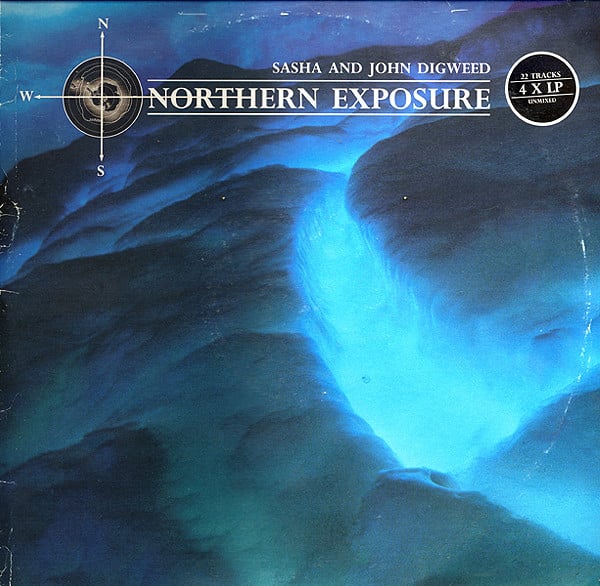

One of the UK’s largest progressive labels, Hooj Choons, had already been pushing early variants of progressive trance, having released material such as Tilt’s ‘Dark Science’ E.P., but it was the 1996 release of ‘Northern Exposure’ by Sasha and John Digweed that really put progressive on the map. ‘Northern Exposure’ is a ground-breaking double CD mix series that weaves in and out of genres, seamlessly blending progressive house, techno, progressive trance, and ambient music.

The Late 90s and Trance’s Rise to Supremacy

As artists like Oliver Lieb, Breeder, and Tilt continued to explore the deeper, more progressive side of trance, soon-to-be world-renowned artists, such as Paul van Dyk, Tiësto, and Armin van Buuren, were pushing a more high-energy sound. Anthemic choruses, crescendos, drum roll build-ups, beat free breakdowns, and heart-tugging refrains created the sound of the mid-to-late 90s, giving rise to the term “uplifting trance”.

Uplifting Trance – In a State of Euphoria

Uplifting trance, also known as “anthem trance” or “euphoric trance”, is strongly influenced by classical music. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, leading artists like Ferry Corsten, Push, Armin van Buuren, Tiësto, and Rank 1 catapulted this form of trance to meteoric levels, especially in the UK, Germany, and the Netherlands.

This type of trance features longer major chord progressions across all elements (lead synth, treble, bass), breakdowns are extended, and the arpeggiation (the melodic part of the song, usually consisting of “saw synth/square lead” sounds) is relegated to the background, as wash effects are pulled to the fore (the harmonic element of the music, or “background fill”, which is often made up of synth choir/vocal/string chord progressions).

Uplifting trance uses similar chord progressions to Goa trance, but, in contrast to the darker tone of the Goa sound, the chord progressions tend to rest on a major chord, with the balance between the major and minor chords determining how “happy” or “sad” the progression sounds.

The “supersaw” sound started to gain prominence in 1998, following the 1996 release of the Roland JP-8000 analogue modelling synthesiser, which was programmed to use a single sawtooth oscillator to emulate the sound of multiple.

1998 – The Beginning of the Golden Age

1998 saw a huge surge in the popularity of trance, thanks in part to a great improvement in the quality of ecstasy available, in the form of the Mitsubishi pill. During this time, the atmosphere in clubs morphed in sync with this drug development, seeing a return to self-love on the dance floors, reminiscent of the late 80s and the “Second Summer of Love”.

This flood of high-quality E, after years of poor and unreliable products, brought with it a chemical desire for euphoria and a heightened abandonment of reality—a gap left in the market by late 90s jungle, drum and bass, and techno. Trance from this era tapped directly into people’s emotions, with Tracks such as ‘For an Angel’ by Paul van Dyk were iconic, often included in popular trance mix compilations of the era, symbolizing the euphoric energy of this golden age.

Songs like Binary Finary’s ‘1998’, which was remixed by rising trance stars Paul van Dyk and Matt Darey, helped to push trance firmly into the limelight, becoming a key genre staple on many dancefloors.

The Unstoppable Rise of Trance 1999

In 1999, trance was unstoppable. Tracks such as ‘Protect Your Mind’ by DJ Sakin and Friends reached the Top 5 in both the German and UK singles charts, with British producer Lange on remix duties.

The instantly recognisable ‘9pm (Till I Come)’ by ATB reached Number 1 in the UK that same year.

Rank1’s hit ‘Airwave’ — which, in 2011, was voted the best trance track of all time — also reached the UK Top 10 in 1999.

But nothing signalled the acceptance of trance into the mainstream so much as Binary Finary famously performing on Britain’s leading music-based TV show, ‘Top of the Pops’.

The dominance of trance throughout the late 90s spearheaded one of clubbing’s most notorious and prosperous eras: the Superclub Era. As of the mid-to-late 90s, the anarcho-capitalist and, in many cases, criminal chaos of the early 90s rave scene had been replaced by a hugely profitable clubbing industry, with new state-of-the-art, high-capacity nightclubs popping up all over Europe. Gone were the days of UK ravers driving round the outskirts of London in search of illegal raves, and in their place emerged large-scale, professionally equipped spaces where people could dance, legally and freely.

Many globally recognised dance brands such as Cream, Gatecrasher, and Godskitchen made a name for themselves through these new superclubs. Indeed, they gathered such an intense and dedicated following that many revellers were seen with the infamous Cream logo or Gatecrasher lion tattooed on their body.

Gatecrasher

From its spiritual home in Birmingham, to its first official venue in Sheffield and beyond, it’s just not possible to talk about superclubs without mentioning Gatecrasher. Starting as a one-off event in Birmingham in 1993, Gatecrasher—the brainchild of Scott Bond and Simon Raine—rose to fame in the 90s and soon became synonymous with the trance sound.

Due to the success of subsequent events, Gatecrasher bought their first venue in Sheffield in 1997, with Judge Jules as resident DJ.

But Gatecrasher’s influence wasn’t limited to nightclubs and one-off raves. In 1999, Gatecrasher released ‘Gatecrasher Wet’, a 2-disc compilation mix showcasing some of the greatest trance hits of the time. This album is widely considered one of the best dance music compilations from the late 90s.

As well as releasing a slew of highly sought mix compilations, Gatecrasher unleashed a new subculture in the form of “Crasher Kids”. Crazy, brightly-coloured outfits complete with glowsticks and dyed hair, and youths dressed as dummies, cyborgs, or anything futuristic, dominated the dancefloors at Gatecrasher events—a stark contrast to today’s all-black techno enthusiasts. Much of this was fuelled by the mass consumption of the aforementioned Mitsubishi pills, which spawned popular sayings like “havin’ it large” and “never too many”.

Cream

But perhaps no brand is more synonymous with 90s trance than Cream. Founded by James Barton, Andy Carroll, and Darren Hughes in 1992, Cream began as a platform for house music in the UK at the now-demolished Nation nightclub in Liverpool. As musical tastes changed during the 90s, so did the bookings at Cream, which brought in Paul Oakenfold— one of trance’s originators—as resident DJ throughout 1997 and 1998.

After asserting itself on home soil, Cream expanded to form Cream Ibiza, extending its legacy to the world’s most notorious party scene. Although it neglected to hold a residency on the island in 2019, Cream is still one of the longest-running club nights in Ibiza, having hosted parties at Amnesia since 1994.

These new high-tech, sprawling venues, paired with the ecstasy-induced worship of music, elevated DJs to almost god-like status, creating the world’s first DJ “rock stars”, the likes of Sasha, Paul Oakenfold, and Paul van Dyk, to name but a few.

Trance 2000

By 2000, trance was on top and had cemented itself as the most popular genre of electronic music in the world. A string of trance records topped the charts across Europe, with classics such as ‘Greece 2000’ by Three Drives on a Vinyl, and ‘Cafe Del Mar’ by Energy 52 first becoming known as big Ibiza club tracks that summer.

Many trance tunes, which had started life as dancefloor fillers during 1999 and 2000, were becoming UK Top 40 chart hits.

Vocal Trance and Commercial Success

Although trance began as an instrumental genre, vocal trance had started to become very popular commercially. A perfect example of this is the Airscape remix of Delerium’s ‘Silence’ which became a landmark track, cementing its place in countless trance mix albums and defining the sound of vocal trance for years to come. Originally released in the summer of 1999, the remix track slowly gained traction and became a worldwide hit in 2000, reaching the Top 10 in the UK, Ireland, Australia, Canada, and the Netherlands.

And, with Madonna choosing to use Above and Beyond’s trance remix in the video for her single ‘What It Feels Like For A Girl’ in 2001, trance had truly crossed over into the mainstream.

The Progress of Progressive

By 2001, progressive trance had begun to merge with deep house and breakbeat to form a new underground dance music sound. This was apparent in music from DJs like Dave Seaman and Hernán Cattáneo. One of the major labels pushing the genre forward during this time was Renaissance with their ‘Renaissance: The Masters Series’ mix compilations.

2002/2003: The End of the Golden Era

Trance had reached peak commercial success at the start of the decade, but, although it remained popular in clubs and continued to sell well, the inevitable backlash began to happen around 2002.

At this time, most of the trance music featured in the charts was very commercial in nature and was no longer reflective of the ethos that originally gave rise to the genre. This new breed of trance, pushed by artists such as Flip & Fill and Ian van Dahl, was commercial and corporate in nature, and it spread across Europe, thanks to satellite music channels, such as Onyx.tv, Viva, MTV2 Pop, and TMF.

Interestingly, instead of trance being superseded by another dance genre, as had been the general rule of dance music succession during the 1990s, an overall backlash against dance music occurred between 2002 and 2007. This was especially notable in the UK, where there was a revival of guitar pop and indie rock, and electronic music was forced back underground. By the end of 2003, there was a widespread decline in UK superclub attendance.

During this period of forced hibernation, trance music evolved to spawn several new subgenres, each with their own distinct style, for example, hard trance and tech trance.

2003: The Rise of Hard Trance

On the opposite end of the spectrum from commercial trance was hard trance, which developed during 2001-2003 as a fusion of hard house and trance music.

Hard house was already a popular sound in the UK, with most tracks featuring rave and hoover samples; a far cry from the commercial sound of the time. Between 2000 and 2001, some hard house DJs and labels—notably Lee Haslam, Scot Project, BK, Andy Farley, Tidy Trax, and Nukleuz—started to tout their take on trance, which influenced the scene. As these producers started to sense that the trance of old was becoming more too commercial, they retaliated with a harder, more minimal sound, and, by 2003, hard trance had become one of the most exciting sounds on the dancefloor.

During what are considered “The Glory Years” of hard trance (2002-2006), Tidy Trax released the ‘Resonate’ mix album series, which illustrated the development of the style over this period. The album series features the heavy use of supersaw arpeggios, as well as prominent kick drums and hi-hats.

2006: Tech Trance

By 2006, the most popular variation of trance was the tech trance subgenre, pioneered by the likes of Oliver Lieb and Marco V.

The defining features of tech trance are its complex, electronic rhythms, which are borrowed from techno and usually driven by a loud kick drum; as well as the filtered, slightly distorted or dirty hi-hat sounds and claps; harder synth sounds, often with a large amount of resonance or delay; and minimal pads, which are usually sidechained to increase the volume of the beat.

Although earlier forms of trance music customarily featured piano, strings, or acoustic guitar, tech trance almost exclusively features synthesised sounds. Tech trance producers were the first to bring prominent sidechaining* into their productions. Sidechain pads were introduced around 2004 and by 2010 many tracks were using the sidechaining technique.

A great example of tech trance from this era is Marcel Woods’ 2006 remix of the Ferry Corsten track ‘Whatever’. The remix featured subtle changes in pitch throughout, The creative use of reverb was also a feature pioneered by the genre, for instance, introducing a big reverb on a snare sound, which suddenly disappears the next time the snare is played, only for it to return shortly thereafter.

The So-Called “Death of Trance”

As of 2020, millions of people around the world regularly tune into Armin van Buuren’s ‘A State Of Trance’ show, and record labels like Armada, Pure Trance, and Black Hole Recordings have a constant flow of new releases. Moreover, in recent times, techno artists, such as Ejeca (under his Trance Wax alias), Nina Kraviz, and Charlotte de Witte, have turned their attention to the vast array of trance releases from the 90s and early 00s, skilfully weaving them into their sets. So, where did the notion that trance died come from?

It’s difficult to pinpoint the exact moment when trance “died”, but many people highlight the period between 2005 and 2006. As previously mentioned, the commercialisation of, and general backlash against, dance music played an instrumental role in the downfall of trance. As with dubstep after it, trance’s move from the underground to its saturation of the mainstream eventually forced people away, because the cheesier, more pop-focused records being produced were in direct contrast with underground dance music culture.

Between 2004 and 2005, commercial and vocal trance became less common on European music channels, which coincided with Viacom UK (MTV/VH1) taking control of both TMF Nederland/Belgium and VIVA Germany. The music channels changed their playlists to place more emphasis on other musical styles, such as US hip hop and contemporary R&B, as well as British electro, and local rap and hip hop music.

Additionally, ecstasy became increasingly harder to get hold of and ketamine began to re-enter clubland in its place. This drug is the polar opposite to euphoric ecstasy and much more suited to the wonky dubstep basslines that eventually gripped the UK.

In March 2012, BBC Radio 1’s Judge Jules—a long-standing bastion of trance music—was replaced by two dubstep producers, Skream and Benga, for the highly coveted Friday night slot. This was essentially the death knell for trance in Britain. With the genre having seen a general decline for several years, and with dubstep on the rise, this programme cancellation was the last nail in the coffin for trance as a mainstream dance style.

This can be seen as a natural progression, since Radio 1’s Friday night dance music programming has always aimed to provide an accurate reflection of the current dance music climate, and those who had grown up on trance were by that point the older demographic, with the younger crowds being more interested in dubstep and electro.

In addition to this, the big room boom and the sudden rise of commercial EDM—especially in the United States—subsumed trance under the same umbrella, a problem which was exacerbated by veterans of the genre, like Tiësto, leaving the genre that made them famous behind entirely.

The Legacy of Trance

Arguably, a great deal of today’s trance music has lost most of its 90s roots and places too much focus on the “drop”. Trance in its pure, original form thrives in an environment where it’s allowed to breathe, build, and progress, which doesn’t necessarily appeal to younger audiences who desire instant gratification from their clubbing experience.

However, the new generation of trance DJs, such as Cold Blue and Factor B, continue to produce and tour the world. Trance never ceases to evolve, mutate and spawn new subgenres, and most likely never will. As the famous saying goes, “Hardcore will never die”, and trance, much like it, won’t either.

Give Trance A Chance - The Mix Series - Episode 16

On this 16th edition, it’s our pleasure to hand over the turntables to one of France’s busiest and fastest rising Djs, Angie. Co-founder of the Female electronic music collective Club Sauvage and Régalade Paris, she’s no stranger to 90's rave, trance, progressive and everything in between and so, across the next 60 minutes, expect a banging mix of classic trance anthems.Tracklist available here.